A Re-Consideration of a Canonical Presocratic Dilemma

Existing in-Between a Changing Sensorial Logos and a Fixed Logical Mindset

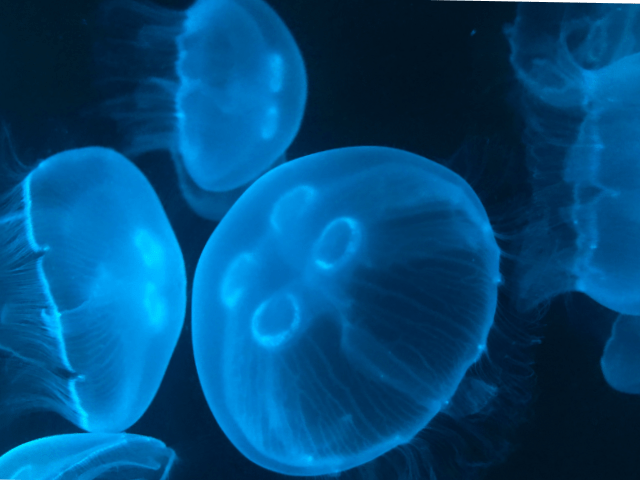

Once we are immersed in a cosmic perception of time, twenty-seven centuries sound like a mere blink of the eyes. Or as the image above may suggest, all those centuries altogether may resemble the skillful, velvety, and instantaneous impulse of a jellyfish in the dark depths of the ocean. Something alike to an electrical flashing that takes place only in one single instant of Absolute Time.

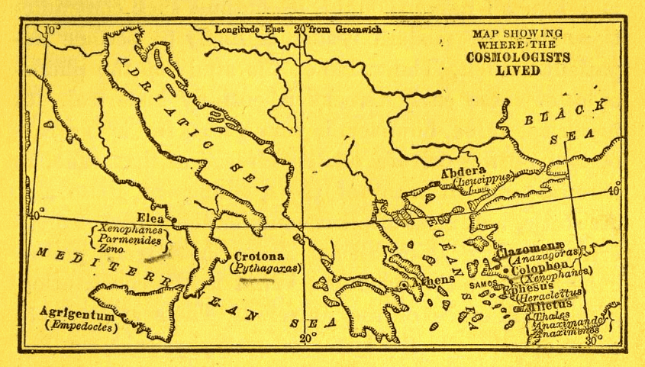

Despite that, It was twenty-seven centuries ago that humanity witnessed, at least in the mindset of a few thinkers that have survived up until the post-modern times that we are navigating with exceptional diffculties, the first Rennaisance of the human spirit. Amidts the confusion and awe that both nature and the human senses awoken in the perception of reality of those thinkers that we know as The Presocratics (sometimes also refer as the "cosmologists"), that first human Rennaisance defined many of the certainties that the thinkers that followed them pondered as passages of initiation into a new form of existing within oneself and among those who we keep perceiving as our human peers.

The Presocratic age was defined by the strong conviction of rendering cult to our sensorial curiosity and the impact that nature had in our senses, instead of giving ourselves up to preconceived theological coded forms of understanding reality which, in turn, made our natural human curiosity dormant and submissive. This first Rennaisaince of the human spirit didn't happen at a random place nor was the consequence of a single set of neural evolutionary transformations. It happened within a specific geophysical space where the natural elements collided as their most organic form of revealing themselves to the human senses.

Thus, light and its reberverations revealed to human sight forms, angles, linear and non-linear obsessions that caught the curiosity of the few thinkers, among the forgotten ones, who belong to the Presocratic "free-thinking and free-sensing gang." Furthermore, as these free thinkers wandered around their respective geographical spaces, their sensorial interactions with the elements that Empedocles from Agrigento, in today's southwestern Sicily, declared as the material essence of all forms of matter.

This way, the mere touch or admiration of the constant motion of the surface of the ocean, or the feeling and aromatic textures that the wind brought to their existance, or even the simple fact of realizing that they were in constant touch with the earth in each step that they endured, radically transform their understanding of the experience of time, space, distance, and inner dialogue as if in these processes was ciphered the meaning of being human, free, and open to the transformations that nature constantly rendered vital thanks to the free exercise of their senses.

Since my late childhood (Middle School), I was exposed to the Presocratic wonders. My favorite thinker, inventor, and risk-taker was Thales of Miletus, born in what today is Turkey, back then part of Ionia, in Asia Minor. His experiments with amber, which through the process of both frictioning and rubbing amber, a fossilized tree resin, with other "natural fossiled gems," led him to one of the early scientific processes of producing electricity. The idea of a man nurturing his curiosity in such a strange and awesomely manner, away from the superstition of medieval alchemists that proliferated many centuries later, got such a hold of my childish curiosity that it was common, while I was unsupervised, that I made my own risky experiments, only out of curiosity, with lightbulbs, wires, and high volumes of electricity that emerged straight from electrical contacts. I produced a few explosions, and luckly I was always cautious enough to take my distance to avoid any damage to my skin or body. But the curiosity was there, similar to the one that I experienced each time that I witnessed thunder and lightning in rural areas where I was able to sense that the massive amount of electrical power had reached a nearby place, probably a forest glade or, even better, the wild surface of the deep open ocean.

Nevertheless, when I suggest "Existing in Between a Changing Sensorial Logos and a Fixed Logical Mindset," I obviously refer to the canonical dilemma that entangled Heraclitus and Parmenides as one of the most exciting early chapters of early western philosphy, perhaps even the preface of it. Both of them were free-thinkers who experienced reality and discovered nature and socialized with people in the eastern oceanic microcosmos of the Mediterranean world. Heraclitus lived in Efesus, in what today is a corner of the Turkish region of Izmir; Parmenides, as if even geography had made them irreconciliable thinking warriors, lived in Elea, right on the opposite side of their Mediterranean microcosmos, back then a region of Magna Graecia, but today a meridional region of the Italian peninsula, somewhere located near modern-day Naples.

Both, if they had been forced to engage in a battle of ideas, would've articulated and orchestrated a Byzantine discussion, somehow anticipating that long argument and digressive maneuvers were going to spread beyond Byzantium in order to shape many of the idiosyncracies of imperial Romans. Their discussions would've shuffled a wide array of ideas on the matters of natural and human metamosphoses, the sensitive logos inherent to the human spirit, and the applications of a fixed logic to understanding reality without surrendering to the transient effects that the natural elements project onto our logical and sensorial reasoning. However, an early form of einfühlung was already present in their approaches to reason and the sensorial acquisition of knowledge.

Modern thinkers like Wilhelm Worringer linked the experience of einfühlung to our exposure to abstract, yet cognizant unatural human constructions made through various historical periods and civilizations, such as the impression that a cyclopean pyramid or a temple with corinthian or doric columns, each suggesting a different kind of order, impress in our senses as the means to rationalize our human condition. Heraclitus saw reality as a flowing river that by the simple fact of having flowing waters suggested that reality, even if we perceived it as unchanging, was entangled in a perennial process of inevitable changes. Thus, the illusion that the waters of a river were always the same was only the expression of an anxiety to perceive long-lasting processes in the reality and life that we are constantly experiencing.

Parmenides, who in a novella by hyper-prolific Argentinian novelist César Aira, dies by the kick of a donkey while he's exiting a tavern so drunk that death happens to him as a scene that suggests that Heraclitus's sensorial philosophical system was indeed right, even though Parmenides believed in a fixed logical system that allowed him to anticipate what was coming next, thus discarding the constant fluctuations that our senses perceived as an elemental configuration of our human condition. Aira's tribute to Parmenides in his homonymous novella is also a form of mocking him, as if by getting trapped in his uncontrollable and transient senses due to drunkenness, he wouldn't have been able to acticipate the pathetic end of his life. An ending somehow similar to his incomplete poem, which he couldn't conclude as he wasn't able to either find the time to finish it, or find the words that he was yearning for, or he simply couldn't enact the logical fixed logical coherence that he professed in his incomplete master///piece (slashes used with the purpose to establish a departure from mastery and the composition of a complete piece, sic).

Perhaps the future that is awaiting us in this ever-changing layered reality, where the mere action of looking around, with the intention to seek something that is no longer there, is enough to force an undesired change in our vital experience, will entangle the entire planet in a set of inconsequential biological and epistemological dilemmas. The 21st century seems the scenario where the canonical Presocratic dilemma, that entangled Heraclitus and Parmenides forever, has been revamped by the energies of history into a renewed virtual and imaginary battle between Henri Bergson and Gaston Roupnel regarding the perception of time, with Gaston Bachelard as the inequivocal referee of a battle where the boxing gloves have been transfigured into malleable tongues that through constant wet blows and puddles of saliva make us experience a constant kick in our heads by a donkey's hoof.

As a corollary, those of us who live in megalopolis, once idealized spatial monopolies of resources and "knowledge," are now beginning to yearn for what we never had: An organic relationship with Nature. In the meantime, the natural forces are sweeping away entire suburbanized spaces. P.S. The first and last time that I saw a donkey was in Morocco, a place where at least we are all protected against the margin of sensorial error that drunkenness grants to those who exit a tavern with the spurious conviction that they will make safe and sound their way back home...